Notes From a Nurse Turned Legislator

Stella was her mother’s name, said former Maryland Sen. Shirley Nathan-Pulliam, DPS (Hon.) ’23, DHL (Hon.), MAS, BSN ’80, RN, FAAN, an inaugural UMSON Visionary Pioneer, but it’s also what she called a pivotal character in her autobiographical book released this year, "Saving Stella: Notes from a Nurse Turned Legislator." The woman, a former patient during Nathan-Pulliam’s career as a bedside nurse, was “a change in direction for her career,” she said, when she began focusing on activism for health equity.

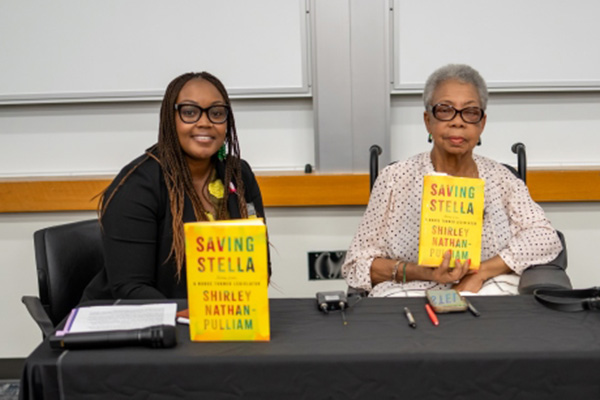

Nathan-Pulliam addressed an audience of UMSON faculty, staff, students, alumni, and others close to the former senator, whose name graces the façade of the UMSON building in Baltimore, during a book-signing event May 21 for "Saving Stella" in that same building, hosted by the Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion for its national award-winning Booked for Lunch book club. Yvette Conyers, DNP, RN, FNP-C, CTN-B, CFCN, CFCS, CNE, FALDN, assistant professor and associate dean for equity, diversity, and inclusion, moderated the discussion.

The book is presented in three distinct parts — Nathan-Pulliam’s early career, her community activism, and her legislative activity — and Stella appears in the first segment. “When I met Stella, I was a team leader on a unit at Bon Secours Hospital,” Nathan-Pulliam recounted during the event. “As I was washing her arm, I felt her breast was hard as a stone.” Nathan-Pulliam went on to explain that Stella had no job and no money; she was waiting to secure a job to have the funds necessary to see a doctor.

This was distressing to Nathan-Pulliam, who came to the United States from England, a country with socialized health care, in 1960. “There, everyone was taken care of,” she said. “That kind of stuff stays with you. What upset me most is she had been in the ER and no one had felt that breast. She hadn’t been examined properly — that’s where the health disparity comes in.”

Nathan-Pulliam also discussed her childhood in Jamaica, when she struggled with dyslexia. She couldn’t distinguish certain letters from others, and her father “called her a dummy” and embarrassed her at the dinner table because she wrote letters backwards, she said. When she eventually earned her Master of Applied Science degree from Johns Hopkins University, her father said, “Shirley, you can stop trying to prove me wrong,” she relayed.

Not wanting to stop and driven by the inequities she saw as a nurse, she ran for office as a state delegate in 1986 and lost. “Yes, I grew up in a third-world country, but where I saw real poverty and hunger was right here in Baltimore,” she said. “I had a burning sensation that there was something else that God wanted me to do.” In the year she ultimately won the election, 1994, five nurses ran for office, and four won, she recalled. During her nearly 25-year career as a legislator, ultimately as a state senator, she faced “political battles, strategic alliances, and landmark bills,” according to the description by Johns Hopkins Press, the book’s publisher, that “provide insight into the art of governance and politics and the power of courage, perseverance, and remarkable compassion in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges.”

“Educating legislators who come from all over is critically important,” Nathan-Pulliam said during the event, recounting an occasion during which a legislator physician disregarded the importance of cultural competency. “I got so mad at him that we wound up in the chairman’s office,” she said (a response akin to winding up in the principal’s office). And yet, she said, doctors now have to complete courses in implicit bias before they take the boards. On another occasion, when Nathan-Pulliam was co-sponsoring a bill to allow nurse practitioners prescriptive authority, she was seeking support and backing from a fellow legislator. “I followed that poor man all the way up the steps,” she said with a laugh. “I went over all the things nurses stood for.”

Now, Nathan-Pulliam said, we no longer have nurses in the Maryland Legislature. “We urgently need to get nurses elected,” she said, providing some tips for nurses to get involved: start local, at the city council; knock on doors; lick stamps; start learning about all the things nurses do; and have a message: five or six bullet points, short and to the point. But the most important thing anyone can do, she said, is vote; it’s the most direct way to promote health equity, which has always been her No. 1 issue.

“I can say we’ve come a long way, but we still have a long way to go,” she said.

Following the discussion, she patiently signed book copies for a line of audience members that snaked through the auditorium, taking time to speak with each person and ask: “Are you a nurse? Will you run for office?”